Jan Bergstra & Laurens Buijs

Amsterdam Gender Theory Research Team

We view sexual orientation (SO) as a main topic in theoretical sexology. We want to try to discuss the topic of SO “bottom-up” in a series of blogs (see also AGTRT-BT1).

Read more about our research on sexual orientation:

Sexual orientation: general principles

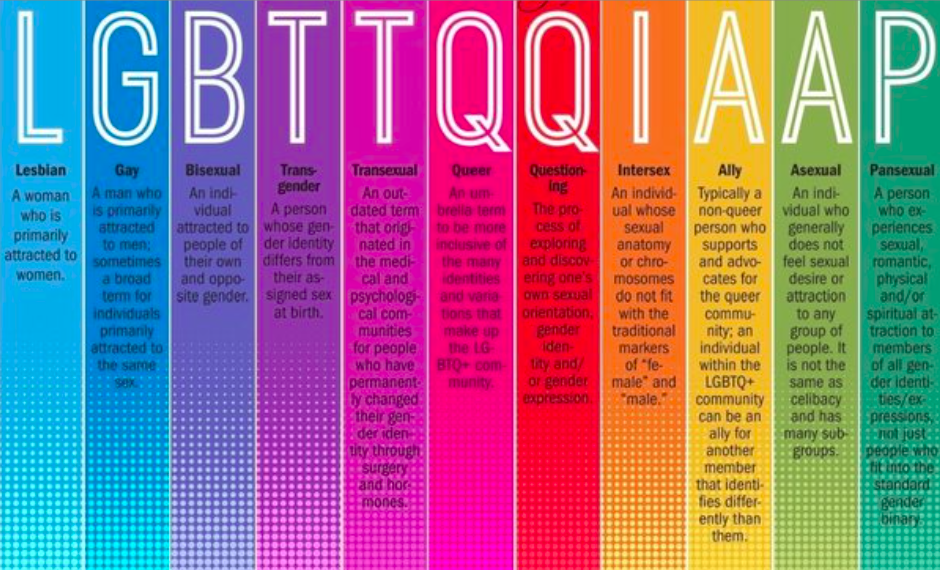

Today, references to ST are most common in acronyms such as LGBT, LGBTQA, etc. Such acronyms provide a compact overview of forms of diversity that one wants to be able to handle in a given context. Using FGT as a starting point, you would want to separate the aspects of gender and sexuality. That consideration leads us to another combination of letters:

T-LHBA-I/N-tgi

Here T stands for transgender, L for lesbian, H for male homosexual (in English one then uses a G for gay), B for bisexual, A for asexual (with autosexual as a subcategory of asexual). I stands for intersex and I/N indicates that intersex is in direct relation to neutral. Finally, tgi stands for all persons with a transgender identity (with no formal gender other than physical gender, as in T).

In part for simplicity, this overview is incomplete: for example, there is no letter D for drag and there is no category for people who want to be male and female at the same time. Some of the list is deliberately incomplete: there is no Q for queer because queer is a meaning that is difficult to fit into theoretical work on SO. It is an anti-category: it is a label that is critical of the idea of labels (and thus a paradox, but nevertheless, or because of it, interesting). In addition, it is a category that speaks out against incorporation of emancipation of sexuality and gender by capitalist interests. For now, we include neither paradoxical nor political categories.

We view asexual (A) as a sexual orientation, as do L, H and B. This is consistent with much of the literature. What is remarkable about asexuality is that the concept of gender plays no role in its definition. That alone is a reason to see and keep A as a category within SO.

We mention T first because transgender persons are formally recognized as such and registered in the population register. The latter is not the case in every jurisdiction, but it is in Western democracies. They have a high degree of protection, but that protection is also under pressure. In some jurisdictions, N is also already regulated by law and well protected.

The category T can be simply described (at time t): all persons who were ever known to the government under a different gender earlier in their lives than at this time (i.e., at time t). The definition of L, H, B and A is much more difficult, and the past 150 years have shown that such definitions do not stabilize easily.

The definition of I (intersex) is based on physical characteristics and the definition of N (neutral) is actually still evolving.

Problems with the description of LHBA exist on several fronts. We list some issues here in no particular order:

- Classically, the question is whether it is actual behavior or a possible unrealized tendency to behave. And when it comes to behavior, is incidental behavior sufficient for classification?

- Why is there no He for straight?

- If there is gender N, do we also know T (ternary) for people who also fall for N persons?

- Robin Dembroff believes LHB incorrectly states the main point. There is a heteronormative bias in this terminology in that, for example, a woman who is attracted to men is viewed differently (as heterosexual or as B) than a man who is attracted to men.

- Incidentally, the T of transgender also implicitly includes not mentioning the C of cis-gender. How to avoid basing indications of diversity on normativity?

- Als we voor een gegeven gender G de uitdrukking AT-G lezen als “is aangetrokken tot G” ontstaan drie SO’s: AT-man, AT-vrouw, en AT-neutraal. Dit zijn monadische noties van SO, waarbij L, H en B dyadische noties van SO zijn. Is het gewenst om zowel monadische als dyadische definities van SO gelijktijdig te ontwikkelen, en te gebruiken, of is de traditionele focus op dyadische definities geen probleem?

- Straight then becomes, for example, “(male and AT woman and not AT man) or (female and AT man and not AT woman).”

- L becomes “wife and AT wife and not AT husband.”

- G becomes “husband and AT husband and not AT wife.”

- B becomes “(male or female) and (AT male or AT female).”

- A becomes “(male or female or neutral) and not AT male and not AT female and not AT neutral).

- In definitions of SO, how to deal with the fact that the concept of gender is evolving? What dependence of notions of SO on an underlying concept of gender can still be handled?

- What role should sexual attraction play in addition to sexual orientation? This distinction is relevant within ABGT because (viewed from the framework of ABGT) sexual attraction can only occur between a person with a male and a person with a female secondary gender identity (SGI, see also AGTRT-BT1).

- In the case of monadic definitions, is it desirable to distinguish within each category AT-m, AT-v and AT-n between the SGI of the person to whom one is attracted, i.e. persons with a male and persons with a female SGI?

- In the case of dyadic definitions, is it desirable to indicate within each category L, H and B which SGI the person in question has, i.e. a male or female SGI?

- In what situations is it appropriate not to mention sexual orientation as a relevant category at all, but to speak only in terms of sexual attraction? In that case, for example, gay men, bisexual women, bimans and heterosexual women with female SGI are in the same category (i.e., female SGI).

At this time, we cannot answer all of these questions. But we assume that in time, descriptions of SO will assume the hetero perspective less than they do now. We call the dyadic descriptions of SO heteroperspectivist, which is different from heteronormative. On the contrary, the monadic descriptions are not heteroperspectival.

Another issue that requires attention is the logic used. Consider the following statement B: “a gay man is exclusively attracted to men.”

Is such an assertion B already true when the assertion applies to most gay men, or must B really apply to every gay man? We assume that it pays to be intentional about this and to make it clear both in assertions and in definitions whether hard universal validity is required or default logic that can tolerate exceptions without difficulty.

Back to the letter combination: T-LHBA-I/N-tgi is “better” but is of course unmanageable in practice, a compromise with readability is in order. We are not there yet.