Jan Bergstra & Laurens Buijs

Amsterdam Gender Theory Research Team

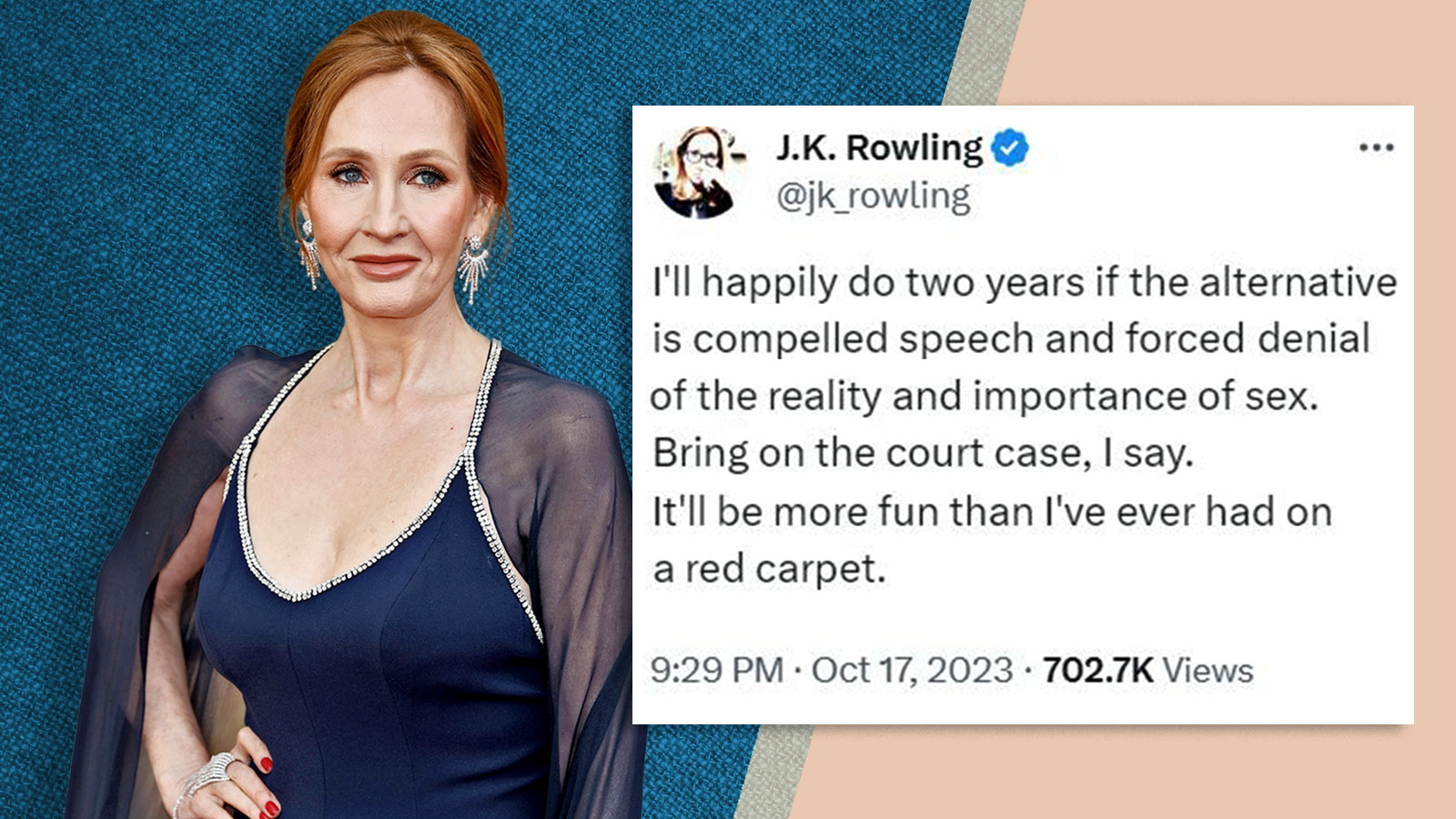

There has been a recent commotion about new legislation in Scotland punishing misgendering. J.R. Rowling made herself heard by naming on X people who have a female gender identity and claim to be transgender, but whom Rowling claims are men (see also AGTRT-BF60). Rowling thereby criticized the new anti-discrimination legislation, and was joined by Prime Minister Sunak.

Read more about Rowling’s fight against transactivism:

The battle between Rowling and Willoughby in 12 points

Meanwhile, unlike before, Rowling takes an essentialist and transexclusive position, which in our view is an incorrect position as we have already discussed in a number of Dutch-language blogs and English-language texts. That Rowling is doing this is understandable. After all, even when her gender-critical position was more nuanced, she was accused of being transexclusive (transphobic, antitrans), when that was absolutely not the case at the time (see AGTRT-BF12).

Read more about the problems with radical transactivism:

Transactivism preaches inclusion to mask a systematic practice of exclusion

Here Rowling is contrasted with Judith Butler (see also AGTRT-BF73) who thinks in the opposite co-essentialist way and equates gender categorization with gender identity, with the latter determining the former. Rowling versus Butler is the public counterpart of Dembroff versus Byrne, the controversy we discussed in AGTRT-1 and AGTRT-4. We are working on a MotR variant of gender theory that provides a workable middle ground between essentialism and co-essentialism (see AGTRT-BF21).

Read more about Judith Butler’s latest book:

Who is afraid of gender? Judith Butler is apparently “afraid of gender”!

This is where the style of BGI(Butler’s Gender Ideology, as described in AGTRT-BF73) avenges itself. Anyone who does not fully agree with Butler is dismissed in BGI as incompetent, uninformed or malicious. There is no need for someone like Rowling (unlike, say, Kathleen Stock, see AGTRT-BF67) to be intimidated by that. Rowling does not fail to point out the incorrectness and undesirable consequences of the co-essentialist position. And in doing so, it clearly puts its name and its economic independence and claims, well with some right, to stand up for women in weak positions (including the women in a women’s prison).

Because we are pursuing an intermediate position, we can in principle refrain from taking sides in Butler versus Rowling and Dembroff versus Byrne, but that is also somewhat noncommittal. We believe that if we had to choose here, the combined arguments of Rowling and Byrne are much stronger than the combined arguments of Butler and Dembroff.

But it does not follow from this for us that Rowling and Byrne’s transexclusive position would be the right position; it really could be and should be different. A middle position is possible, tenable and desirable.