Laurens Buijs

Amsterdam Gender Theory Research Team

Gender neutrality has been the new ideal in the emancipation of sexuality and gender for several years. This is evidenced in part by the fact that an increasing number of young people identify as non-binary, a label born of the belief that the dual distinction between masculine and feminine is inherently oppressive. Increasingly, therefore, gender empowerment is focusing on brushing away this duality. But while neutral gender certainly occurs in exceptional cases, the rise of non-binary gender seems largely a hype. Moreover, gender neutrality need not be seen at all as an alternative to the distinction between man and woman, but rather as something that can exist alongside it. In fact, we desperately need the labels masculine and feminine in the fight against heteronormative patriarchy. The still fragile emancipation of the LGBT group risks losing out if we step away from it now. Thinking in terms of androgyny may be a solution to the challenges now facing the gender diversity movement.

Structure of this article

- The rise of the gender-neutral ideal

- Essentialism versus constructivism

- How constructivism can spill over, and how to avoid it

- Interdisciplinary insights on gender

- 4a. Primatology

- 4b. Evolutionary Biology

- 4c. Psychology

- 4d. Anthropology

- Gender neutrality and the struggle against patriarchy

- Gender neutrality in transgender emancipation

- Gender neutrality in intersex emancipation

- A better alternative: androgyny

1. The rise of the gender-neutral ideal

For several years now, gender emancipation has taken a new path: that of gender neutrality. One of the first signs of this was when diversity officers at the Dutch railway NS decided that travelers would no longer be addressed with “Ladies and gentlemen” over the intercoms at stations, but with “Dear Travelers.” Meanwhile, entire groups identify themselves as non-binary (neither male nor female), gender-neutral restrooms pop up like mushrooms, and we see more and more people wanting to determine their own “pronouns”.

On social media and at some educational institutions (especially universities), among others, it is becoming a new norm that another person’s gender is no longer assimilated, but that everyone decides for themselves which pronouns they want to be addressed with: he/him, she/her, or the gender-neutral “they/them”. So the ideal of gender neutrality is translating itself into our everyday living world in all sorts of concrete and tangible ways.

Gender-neutral thinking did not come out of the blue. Ever since the beginning of women’s emancipation, feminists have been arguing with each other about how the struggle against patriarchy should be fought. There has always been a current that has seen the root of the problem in the fact that we distinguish between masculine and feminine in the first place.

2. Essentialism versus constructivism

In feminism’s second wave, feminists opened the attack on gender as essences fixed in nature. The conservative idea of “the man is just like this, and the woman is just like that,” came under fire with an appeal to the large role culture plays in how we interpret masculinity and femininity. The idea that there is such a thing as the culturally constructed “gender,” which is something other than the naturally formed “sex,” was eagerly embraced by feminists. Thus stood a battle between essentialist and constructivist conceptions of gender.

The idea of gender as a construct was increasingly developed in the social sciences during the 20th century. Influenced in part by the work of Simone de Beauvoir, women’s disadvantaged position was no longer explained by their being the “weaker sex,” but because our culture pushed them into a disadvantaged position. Partly through her work, the idea began to grow that gender in the foundation is not something natural, but something social. The famous phrase from her book The Second Sex (1949) would form the basis of modern gender studies: “One is not born a woman, but becomes one.”

The understanding that gender is a cultural product led to a veritable revolution in sociology of gender and sexuality in the 1980s and 1990s. The famous feminist philosopher Judith Butler showed in her seminal book Gender Trouble(1990) that gender does not exist in isolation, but only in social relationships.

Masculinity and femininity, Butler said, are “performative”. They come about in our everyday behaviors. Gender she saw as the consequence of roles we perform according to certain cultural scripts. Butler insisted that we do not just give meaning to gender with our behavior. She went a step further: through our behavior, we actually create gender. Gender is “made” through our performances of it in everyday behaviors, Butler showed. As we act like a man or a woman in all sorts of subtle ways, the world around us starts to mirror that as well. Gender is thus continually produced and perpetuated.

She extended the stage metaphor further in her later work: where roles are performed, the script can also be improvised. If the distinction between male and female is maintained through our behaviors, then we can also undo this strict distinction, by adjusting our practices and behaviors.

A new ideal of emancipation arose from this scientific insight, among other things. Eliminating the distinction between male and female in our social world was increasingly seen as a way to get rid of oppressive and oppressive patriarchal norms. It is this radical thinking that has led to all sorts of excesses in the emancipation movements.

One such excess is the ideal of gender neutrality, which holds that it is possible to move completely beyond the distinction between male and female. The move toward non-binary gender identities is often defended on the grounds that just making the distinction between male and female (or man and woman, or masculine and femininem, for that manner) is a Western and imperialist instrument of power. The “gender binary” would be as oppressive a system as, say, the heteronorm, and so we should distance ourselves from it. But such a line of reasoning is possible only within thoroughly constructivist thinking.

3. How constructivism can spill over, and how to avoid it

Judith Butler’s work can certainly be called groundbreaking. Her central claim that gender is not just socially fleshed out, but is actually “made” and “created” in social practices, is convincingly substantiated. In doing so, she stands in a tradition of other influential philosophers who have shown that our reality is ultimately produced in social networks. She has thus shown how powerful and far-reaching social behavior is, and how even a category like gender – often seen as natural – can yet only come to life in social networks.

Every sociologist who works with gender and sexuality has been influenced in some way by Butler’s work. The idea of “gender as a performance” gives scholars many tools to study how gender norms take root in a society and how they change over time. It also gives feminists many tools in the fight against conservative and essentialist explanations and legitimizations for the disadvantaged position of women.

But constructivism also has a tendency to go into extremes. Within this logic, in recent decades there has been an increasing tendency to assume that if gender is a social construct, then gender can also be “reconstructed” and “reconstructed” at will. The idea arose that Butler had proven that gender is an unwritten sheet, something we can determine and mold entirely by ourselves.

This has led to all sorts of extreme and bizarre assumptions, such as the idea that the penis is nothing but the arbitrary meaning given to it in social relationships. It became taboo within monodisciplinary sociological thinking to explain sex and gender differences by looking at the body. Those who also wanted to look at, say, the role of chromosomes, hormones, genitalia or the brain in how gender differences come about were quickly dismissed as “essentialists”.

Modern philosophers of science, however, have since attacked the dichotomy of “soft” constructivism versus “hard” essentialism. Partly because of the work of Bruno Latour, we have now come to recognize this as a false opposition. Latour saw it as an important mission to limit constructivist thinking in the social sciences. Yes, the world is socially constructed through and through, but that does not mean there is nothing “hard” and “real” about the world anymore, Latour said.

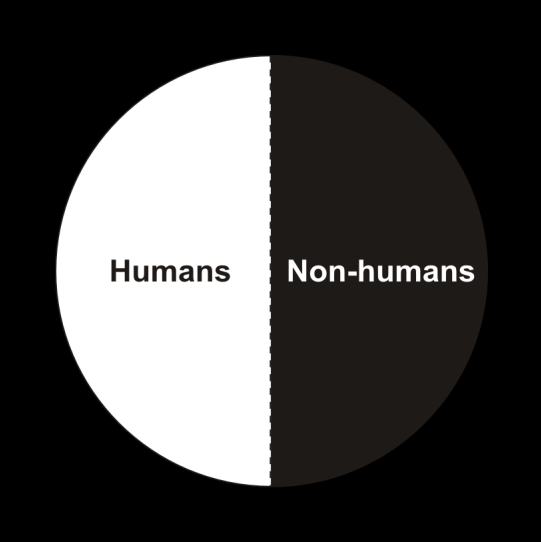

Latour showed that the world is indeed socially constructed, but that the material world imposes limits on our interpretations. In Latourian thinking, material things are fully-fledged social actors, “trading along” like people in the networks that make our world. They are called non-humans by Latour to emphasize the acting and social nature of objects.

Non-humans are always “plural”: there is “stretch” in how they can be mobilized in social networks, but at the same time this stretch is not endless. The material nature of these social actors also imposes constraints on how social networks can engage with them.

A simple example: a chair is indeed a multiple social actor, depending on the network the chair wants to “deploy”. You can sit on a chair to eat, you can stand on it to grab something from a kitchen cabinet, you can use a chair to hang laundry over, but you can’t fly to Turkey with a chair. This insight can also be applied to the social networks that produce knowledge about gender, and the non-humans who “act” in them as social actors.

We can argue, on the one hand, that the differences between masculine and feminine are indeed determined by the historical, social and political characteristics of the social network that gender tries to “produce”. Even material things like genitals, chromosomes, hormones and other non-humans are willing to move with these networks as social actors.

But on the other hand, the willingness of non-humans to move with social networks is not limitless. They also provide “counter pressure,” ensuring that masculinity and femininity cannot be interpreted and constructed in endlessly different ways.

By looking at gender with a Latourian perspective, we start to see that there are all kinds of non-humans in the social networks that impose constraints on how gender can be constructed. There is ultimately something really “hard” about gender, a core that is independent of relationships, power and interpretation. Gender is in part something we “encounter” as people, even before we mobilize it in our networks.

One such “hard” aspect of gender is that the distinction between masculine and feminine simply exists. The constructivist ideal of “going completely beyond gender,” as expressed in the gender-neutral and non-binary movement, is not sustainable with an interdisciplinary gaze that seeks to transcend simplistic oppositions (such as those between hard and soft science, between essentialism and constructivism, between object and subject, between nature and culture). Neutral gender may be applicable as a “third gender” to describe certain exceptional cases of transgender and intersex persons (see below), but they should rather be seen as the exception that confirms the rule. At its core, gender is still binary: we cannot simply brush away the distinction between masculine and feminine.

4. Interdisciplinary understandings of gender

A satisfactory view of gender thus requires transcending the opposition of constructivism and essentialism, and complementing sociological thinking with interdisciplinary insights. Then it turns out that not everything is constructed about gender, nor is the distinction between masculine and feminine so easily abandoned. I will illustrate this here using insights about gender from four disciplines: primatology, evolutionary biology, psychology and cultural anthropology.

4a. Primatology

Through the work of primatologist Frans de Waal, we know more and more about the nuances of gender in primate species. For years, De Waal has played a key role in fighting for a biological science that challenges its own conservative assumptions, and that is more attentive and appreciative of the unprecedented diversity in sexuality and gender among primates.

De Waal has always opposed conservative voices that sought legitimacy for social inequality in biology, or that sought to show that gender and sexuality diversity do not exist among animals. In fact, De Waal sees evidence in the animal kingdom for his belief that human societies can become more open and open-minded regarding gender diversity.

In his latest book, Anders (Different), which deals specifically with gender in primates, he shows that gender comes about through a mix of instinctive and learned behavior. He rejects the idea that in the animal kingdom there is some sort of uniform division of roles between the sexes. Each species of primates arranges gender differently: among chimpanzees, the males are in charge, but among bonobos, the females.

Even within the species, typical male and typical female behaviors are not as fixed in DNA as we often used to think, De Waal concludes. Both chimpanzees and bonobos take about 16 years to reach adulthood, during which time they adopt a lot of learned gender behaviors from older apes.

At the same time, instincts also play a role. “Give a group of young chimpanzees a pile of toy cars and dolls, and the lot is quickly divided: the boy monkeys usually step over the dolls and pounce on the cars, the girl monkeys usually choose the dolls (although they are also quite curious about the cars nicked by boys),” de Volkskrant aptly described De Waal’s findings.

In conclusion, De Waal observes that there are instincts that humans have in common with apes that meander through our cultural achievements. But he is careful about generalizations about genders. He makes room for gender fluidity and androgyny in primates. For example, he describes the case of gender-nonconforming chimpanzee Donna: a very masculine female. “We primatologists are very focused on typical male and female behavior. It is high time to pay attention to what is in between,” he said in The Parool.

At the same time, he also feels a responsibility to vindicate the constructivist camp in the social gender debate. According to him, the debate urgently needs insights from biology: “We should not pretend that it is about cultural preferences and that we can change the behavior of men and women at will. The question of whether you feel male or female is in your constitution. We are biological beings, we cannot operate unbiologically.”

De Waal builds in a lot of room for diversity and fluidity in terms of gender, but the distinction between masculine and feminine, or male and female, he says, is hard and cannot simply be abolished or dismissed as a socio-cultural phenomenon. “Gender identity is in you,” he concludes based on his work on primates. “People’s flexibility is less than some would like,” he said.

4b. Evolutionary Biology

Evolutionary biology is another field of study that convincingly shows that masculine and feminine are deeply embedded in being human, and that we cannot simply brush these distinctions aside as a social construct.

Evolutionary biology, by the way, is not without its problems in thinking about gender. For example, Charles Darwin wrote in 1871, “The man is bolder, more combative and energetic than the woman, and he has a more inventive mind”. From the beginning, the field has been taunted by conservative and problematic cultural assumptions about gender and sexuality that stem directly from the traditional British class society of the 19th century in which Darwin grew up.

Thanks to queer interventions by evolutionary biologists such as Bruce Bagemihl and Joan Roughgarden, evolutionary biology has now thankfully begun to think much less heteronormatively about the animal kingdom. Masculinity is no longer placed above femininity. In thinking about the role sexuality plays in how species adapt, there is less attention today to the reproductive function, and more attention to the social function of sex. There is more focus on masculine females and feminine males. Moreover, phenomena such as LGBT and drag are now also recognized as natural variations of sexuality and gender among animals.

But even the most queer interpretations of evolutionary biology do not question the idea that masculinity and femininity are ultimately the fundamental building blocks of the evolution of complex social species (see AGTRT-BA2). Their work does not deny the dual distinction, but uses it as an argument for a more progressive view of evolution. Progressive advocates in evolutionary biology emphasize that the binary distinction between masculine and feminine is precisely a necessity to achieve all kinds of variation in sexuality and gender. They point out that from that dichotomy an entire spectrum eventually emerges, and that this diversity gives evolution much-needed color and oxygen.

4c. Psychology

The distinction between masculine and feminine is also difficult to eliminate psychologically. Modern psychology grew out of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and Carl Jung’s analytical psychology. Both saw sexuality and gender as foundations of the psyche.

Nor is the work of these scholars free of assumptions about gender that stem from the conservative society of the early 20th century. Then again, even queer interpretations of the discipline cannot get around the binary distinction between masculine and feminine.

Psychoanalysis has become a lot more open-minded over the years – in part because of the critique of queer theory. Within Freudian thinking, meanwhile, traditional assumptions about the heterosexual nuclear family based on the “oedipal triangle” father/mother/child have been abandoned. Through queer psychoanalysts such as Robert Stoller, the field has come to recognize LGBT as a natural variation. He conducted groundbreaking research on the mental struggles of transgender, drag queens and intersex individuals. His conclusion: their psychological problems cannot be explained because there is something wrong with them, but because society does not take them at face value.

Freudian thinking has fortunately become much less dogmatic in recent decades. But still the insight stands tall that in parenting, the child encounters role models who embody masculinity and femininity, and that how identification with these role models proceeds determines mental development. So the dualism between masculine and feminine still plays an important role, even in modernized psychoanalysis.

Stoller’s work demonstrates this. He concludes precisely from his research on the LGBT group that everyone has a “gender core” embedded in their identity, or in other words, a rudimentary and more or less fixed perception of feeling male or female (what in ABGT is called the primary gender identity, see AGTRT-BF20). This core, according to Stoller, is established before the age of two through a psychological process of “imprinting”. This process is the result of the baby beginning to break free from the symbiotic relationship with the mother, in which hormonal, physiological and biological factors play a major role.

According to Stoller, the attitude of the environment also plays a role in the formation of our gender core, but complex socialization is not yet involved here. The “primary gender identity” that becomes embedded in the core of our personality at an early age is therefore ultimately binary, according to Stoller, despite the tremendous variation in gender and sexuality that exists in humans in addition. Stoller’s work shows that even LGBT people ultimately benefit most from positive identification with this primary gender identity.

Even in Jungian thought, the distinction between masculine and feminine still stands firm in thinking about the so-called “process of individuation. Men encounter their feminine side (their Anima) in their maturing process, and women encounter their masculine side (their Animus). Jungian psychology ultimately revolves around how to integrate this duality into the personality.

To successfully integrate the Animus and Anima into the personality, duality must first be fully recognized and explored, Jung argues. Thus, there is no room for denying or glossing over the duality between genders with Jung. Indeed, one’s own primary gender identity (male or female) is one of the anchors in the Jungian process of shadow work.

Shadow work is about becoming aware and integrating sides of our personality that we have suppressed during our socialization by patriarchy (see AGTRT-BA4, AGTRT-BA7 and AGTRT-BA9). This process of awareness usually proceeds differently in men than in women, as Marie-Louise Von Franz (Jung’s great confidant and successor) has shown. After all, men and women have been traumatized by patriarchy in other ways. If one’s own gender identity is not clear, shadow work also becomes very complicated.

Moreover, the Jungian school has convincingly shown that the Animus and Anima are universal archetypes; symbols that occur in more or less the same way in human cultures around the world. Archetypes, in Jungian thinking, are not merely cultural inventions of people, but deep-seated structures in the collective unconscious. Although each culture naturally shapes the masculine and feminine archetypes themselves, in terms of their structure they are not invented by us, but we encounter them in our consciousness. So we have to relate to it.

Jungian thinking about the Animus and Anima is not without its problems. All sorts of stereotypes creep in quickly about masculinity and femininity. But at the same time, fortunately, all sorts of work has been done in the Jungian field to correct the bias toward the white cisgender heterosexual male, for example by Marie-Louise Von Franz and Marion Woodman. Jungian psychology, with at its heart the distinction between the archetypes Animus and Anima, therefore remains relevant even today. In ABGT, Jungian thought has been adopted and modernized through the concept of secondary gender identity (SGI, see AGTRT-BA24).

Moreover, Jung is not as binary in his thinking as is often thought. He does make room for gender-neutral personhood as well. These Jung also holds in high esteem because they result from shadow work: the integration of masculine and feminine traits. Gender neutrality is thus posited by Jung not as a substitute for the distinction between masculine and feminine, but rather as the consequence of recognizing and exploring this duality.

4d. Cultural Anthropology

To legitimize the rapid rise of gender neutrality and non-binarity, it is often said that cultural anthropology would have shown that the “gender binary” is an oppressive Western construct, and that all kinds of indigenous peoples never lived with this binary before being colonized and influenced by the West.

True, there has been much criticism in cultural anthropology of the Western “gender binary,” but then what is meant by it must be carefully considered. Indeed, in many indigenous cultures, gender roles are not as binary and fixed as in the West. But by that, anthropologists did not mean that in indigenous cultures there was no distinction between men and women at all. It merely means that they interpreted this distinction less rigidly and more fluidly than we do, resulting from the fact that they often lived less patriarchal and more matriarchal lives than we do.

In many indigenous cultures, there is a lot of room for what we now call feminine men, masculine women, transgender people, drag queens and hermaphrodites. But all this diversity can still be seen as variation on the dual distinction between male and female, masculine and feminine.

It seems that the gender diversity and gender fluidity of indigenous cultures may exist precisely because in these cultures there was a lot of attention to the question of what exactly the distinction between masculine and feminine means. They are interested in how many ways we can be male and female, and we can embody our masculinity and femininity. Thus, there is no mass denial of the distinction masculine and feminine in indigenous cultures.

5. Gender neutrality and the struggle against patriarchy

It is time to recognize that the gender-neutral ideal as it is now often formulated, as an attack on the distinction between masculine and feminine that is supposed to be “oppressive,” is an aberration in the emancipation of gender and sexuality. This ideal clashes with insights from a variety of scientific fields, but it also undermines the fight against patriarchy.

First, there is all kinds of evidence that this undermines public support for the LGBT movement. More and more letters are being added to the LGBT alphabet, and with that comes new emancipation demands on society. That society is increasingly dropping out.

People were mostly willing to make room for lesbian, gay, bi and trans, but the idea that they must step into a world where the distinction between masculine and feminine is seen as “wrong” or “old-fashioned” and is also no longer allowed to be reflected in language, many experienced as not only counter-intuitive, but also insulting and oppressive.

Second, the emphasis on gender neutrality deprives us of the very weapons we so desperately need in the fight against patriarchy. Among other things, this is well explained in a classic 1979 piece by Maaike Meijer, now professor emeritus of gender studies. She points out the danger that opening the attack on the dual distinction between masculine and feminine will ultimately put a bomb under the feminist project. I quote:

“I do not believe that one can ever abolish the concepts of masculinity and femininity, any more than one can ever abolish the male body and the female body. Why? Because those concepts belong to the “natural event of the soul. As long as humans has walked the earth she has perceived the sex difference. […] It doesn’t matter either. What does give something is the appreciation then attached to those sets of opposites. […] With valuation, it goes wrong. One half of the contradiction is systematically valued higher, at the expense of the other. That is the essence of patriarchy.

Maaike Meijer (1970)

Abolishing the terms “masculine” and “feminine” – apart from being impossible – is a transparent trick with language. When you agree to stop using these terms, the degradation of the feminine will still continue, with this difference, that even the instrument with which we can talk and think about it has been taken away from us. Language changes only, as reality changes. That process is not reversible. Patriarchy cannot be eradicated by a few artifices in language or by a few agreements that cost nothing.”

Third, it is also not a good signal to the new generation of young people if an overly constructivist perspective on gender is preached in their education. It is great that we are moving toward a world where gender and sexuality are less fixed and surrounded by fewer norms. But young people become unnecessarily confused when they are told the story that anything is possible, even frivolously switching or even inflating one’s primary gender identity. In this way, identification with non-binary and trans can become too much of a hype, and an escape from the difficult personal struggle to explore and accept one’s own body and sexuality.

6. Gender neutrality in transgender emancipation

The emphasis on gender neutrality and non-binarity can be particularly confusing for transgender people, who owe much of their emancipation precisely to binary thinking about gender. In this, the concept of gender dysphoria has played an important role.

Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis for people who often feel from a young age that they were born “in the wrong body,” and who want to switch from birth sex to opposite sex. In transgender people, the primary gender identity does not match the sex of the body at birth. Since the primary gender identity is fixed in the personality from the second year of life, medical “re-assignment therapy” is the only possible treatment for gender dysphoria.

The concept of gender dysphoria has provided much structure and assistance to the vulnerable group of transgender people in recent years. The concept allows them to accommodate and accept their own personal struggles. The concept also allows doctors, psychological counselors and insurers to properly and carefully determine who is eligible for gender reassignment surgery.

Gender dysphoria is about discomfort with one’s birth sex. So it does not mean that everyone with gender dysphoria necessarily wants to adopt the opposite sex. For certain people with gender dysphoria, claiming not male or female but neutral as a gender identity can be quite a godsend. But for most transgender people, it is probably not so complex: they just want to go from male to female, or vice versa.

From progressive and conservative perspectives, there are all sorts of legitimate criticisms to be made of medical gender transitions. There is often criticism from progressive quarters that there is too much emphasis on medical treatments that are offered in too binary a manner. Yet even those “binary treatments” are still, for many transgender people, the beginning of a major positive turnaround in their lives. Finally, in recent years, patients have increasingly had a say in how and to what extent they want to undergo these treatments, allowing more personal freedom than in the past in choosing the most appropriate course of treatment.

But from within the gender-neutral movement, there is increasing pressure to disconnect gender dysphoria altogether from binary thinking about gender. The gender-neutral and non-binary movement is drawing more and more intensively with the trans movement from the idea that they fall under “the same umbrella”. Thus there is unintentional and unconscious pressure on transgender people to stop being binary, or even to identify as non-binary.

The current gender-neutral movement plays into the idea that it is not the transgender person who needs to adapt, but that society needs to be adapted to make more room for identities in between male and female. Do transgender people still want a sex change in a society that has abolished the binary distinction between male and female? That is the question that is then quickly asked; a question that questions the legitimacy of transgender people’s need to change their gender.

It is a good idea to give transgender people more space between male and female, and also to allow some to identify as neutral. There can be all sorts of valid reasons for this. But care must be taken to prevent the criticism of binarity from spreading, when “changing gender” is simply still the best solution for most transgender people. Those individuals may then be given the idea not only from conservative but also from progressive quarters that their sex change is not right or necessary.

7. Gender neutrality in the empowerment of intersex persons

Intersex people are often referred to to make the argument that there is more to life than male and female bodies, and that societal space must be made for them. Persons with intersex are born with both male and female sex characteristics. A closer look at this group, however, reveals that it is more complex after all.

Intersex is not one clearly defined category, but a catch-all for a host of different conditions that each affect gender development in its own way. These conditions tend to lead to significant health problems. For example, girls can be born with Turner syndrome (1 in 2,500 girls). They have only one X chromosome, which can lead to growth disorders, heart abnormalities and kidney abnormalities. In boys, Klinefelter’s syndrome is relatively common (1 in 600 boys). They have XXY chromosomes and this can lead to all kinds of problems during development, for example with speech and language development, IQ, physical growth and expression of emotions.

There are many other possible intersex variations, including Swyes’ syndrome, leydig cell hypoplasia, ovotestic DSD, insensitivity to male hormones and enzyme disorders in steroid synthesis. Each variant has a different impact on the intersex person: sometimes there are visible or invisible mixed gender characteristics, but in other cases there are none. Sometimes there are health and fertility issues, but sometimes not.

In the social debate, the impression quickly arises that intersex is quite common. The rate of 1.7% is often mentioned, but the figure of 1 in 90 also falls quickly, taken from a 2019 Danish population study. The problem with these high percentages is that they are at too broad a definition of intersex are based, because they include individuals who, in the vast majority of cases, can still be clearly categorized as male or female, and who have conditions that doctors also do not consider intersex.

Looking only at the number of individuals where the chromosomal sex does not match the phenotypic sex, or where the phenotype cannot be classified as either male or female, the prevalence is estimated to be about 0.02%. Thus, if that percentage is correct, it is exceptionally rare to have a body that is really completely outside the distinction of male and female. And even then, that does not necessarily mean that the person does not feel like a man or woman either.

Because intersex is so intertwined with struggles of physical health and fertility, it is a medical category more so than, say, homosexuality. Therefore, a large part of the intersex movement’s struggle also focuses on the medical community: for example, they want an end to forced surgeries at birth without the child’s participation, and in a general sense, better medical interventions in which they have a greater say.

Gender comes about through a complex physiological process in which chromosomes, hormones and genes play key roles. The broad spectrum of gender and sexuality that exists at the social and psychological level is simply not seen at the body level. Apparently, our bodies are really strongly inclined to express themselves binary after all, as male or female. Thus, intersex cannot simply be cited as evidence of the existence of a broad spectrum in between the male and female sex that society should make room for.

Of course, norms do play a role in intersex experiences with doctors and family, for example. Intersex persons know very well how overly convulsive the social environment can react to issues that touch on gender, and how great an impact it has on the one who does not conform to prevailing gender norms. It is also clear that there is much to be gained from better educating the general public about intersex and its many variations, as misunderstanding and ignorance can lead to much pain and harm.

LGBT and intersex certainly share the same goals in some ways: together they fight against exclusion and stigma, and for recognition for minorities in gender, sex and sexuality. But the struggle for diversity of gender roles cannot simply be extended to the human body, because biology is simply a lot less elastic than social roles, identities and norms.

There are always exceptions. Within the small group of intersex people, there are those who cannot or do not want to identify as male or female at all, and prefer to go through life as gender neutral. There is nothing wrong with that; indeed, it makes them unique and therefore special. But this does not mean that they are helped by a social emancipation struggle against the distinction between men and women: rather, they are helped by the recognition that they are an exception to this distinction.

8. A better alternative: androgyny

A progressive perspective on gender is and remains necessary. We live in a society that is patriarchal at its core, and that fixes the difference between masculine and feminine too much in nature. This thinking is a major threat to the emancipation of the great diversity in gender and sexuality, which we know well exists in humans but also in the animal kingdom.

At the same time, constructivist thinking about gender also has its pitfalls. This thinking leads to all sorts of excesses, denying the existence of a basic “structure of gender” that is folded into the universe and into ourselves. The idea that merely making the distinction between masculine and feminine is oppressive, as is too often going around in the gender-neutral and non-binary movement right now, is one example.

It is true that our patriarchal society imposes all sorts of stifling norms in terms of gender and sexuality. But that does not mean that the fight against the heteronorm, for example, is comparable to the fight against the “gender binary”. The heteronorm is an oppressive patriarchal system from which we can free ourselves through emancipation. Indeed, the heteronorm falsely tells us that heterosexuality is the only normal and natural order, and bases this on traditional and outdated ideas about masculinity and femininity, as well as sexuality (see AGTRT-BA2).

The “gender binary” itself is not an oppressive patriarchal system, at least not if we narrowly define it as making a fundamental distinction between masculine and feminine, male and female. We have seen that from an interdisciplinary perspective, we simply cannot avoid that distinction. The dualism plays a fundamental role in many aspects of existence: in our development, in our body, in our unconscious, in our identity and in our relationships.

Therefore, even in non-patriarchal societies, a “gender binary” will always exist. However, gender expectations are less stifling in those societies. If there is no longer a hierarchy and power struggle between genders, society will naturally become less frenetic about masculine and feminine, making the distinction only where it is relevant.

But abolishing the concepts of masculine and feminine will never succeed; that is fighting against the cosmic order. Moreover, it undermines the fight against patriarchy. First, it decreases support for the LGBT movement. Second, it deprives us of the language to fight against the overvaluation of masculinity and the undervaluation of femininity. Third, it sows confusion among young people and especially the already vulnerable transgender and intersex group.

So it is time to recognize that the gender-neutral path is an aberration in gender empowerment. That does not mean it is not a good idea to introduce a neutral gender: for certain specific exceptional cases of transgender and intersex persons who do not fit well into the pigeonholes of male or female, that is a suitable label. But the current trend toward gender neutrality and non-binarity, with its sharp attacks on any distinction between masculine and feminine, is akin to political-correctness and hype.

A better alternative is to think about people in terms of androgyny: the idea that every man is also feminine, and every woman is also masculine. The concept of androgyny makes room for the unprecedented gender diversity among people, without being an attack on the binary distinction between masculine and feminine that is now part of our existence. Moreover, androgyny has been excellently researched and substantiated interdisciplinarily, as opposed to non-binary.

Androgyny ultimately underlies the success of homo sapiens. Every human being has an androgynous nucleus (see AGTRT-BA1). This has made our species more empathetic, versatile and social, the very traits that have secured our survival on the Savannah and beyond. But in today’s patriarchal society (which began 12,000 years ago with the agricultural revolution, see AGTRT-BA3), men are poorly in touch with their feminine side, and women with their masculine side. Whether they belong to the LGBT group or not.

Androgyny puts the focus on the gender fluid core hidden in the soul of every human being. Androgyny emphasizes that gender empowerment is an issue for everyone, because everyone suffers from patriarchal trauma (see AGTRT-BA4). Androgyny expresses that masculinity and femininity should not be hidden away but celebrated because gender gives color to life. Androgyny, moreover, can be firmly framed scientifically with insights from biology, sociology and psychology, which means that in discussions about gender and sexuality, we will no longer be so likely to get lost in ideological wishful thinking and extreme constructivism.

Goodbye politically-correct humanity, welcome androgynous humanity!

Leave a Reply