Laurens Buijs

Amsterdam Gender Theory Research Team

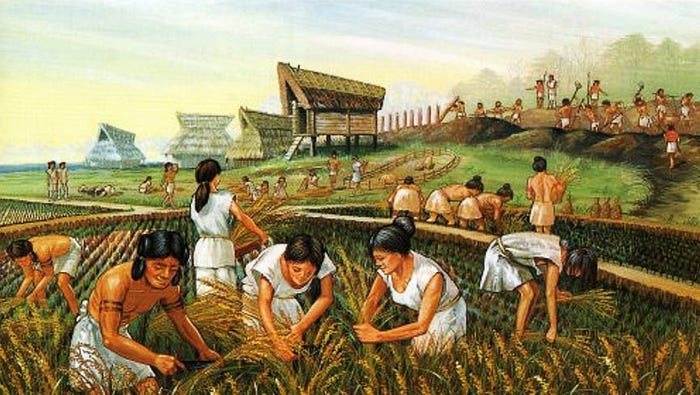

About 12,000 years ago, humans made their greatest cultural shift in the history of our 300,000-year-old species: the Neolithic revolution and the advent of large-scale agriculture heralded the beginning of our patriarchal culture. Humanity traded life in large groups for life in heteronormative nuclear families, based on the father/mother/child triangle. Masculinity and femininity were offered separately in this nuclear family, splitting the growing child’s psyche. This with major implications for our personal development in both gender and sexuality.

Structure of this blog

- Introduction

- The divisive effect of patriarchy

- Growing up in the heteronormative nuclear family

- Healing and integrating a split psyche

- Restoring our multifaceted sexuality

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

In my blog on hunters and gatherers, I argued that Homo sapiens is at its core an androgynous species (see AGTRT-BA1). As our men became more feminine and our women more masculine, the sexes grew closer together and a species emerged with a previously unseen capacity for cooperation. It is precisely this exceptional ability to cooperate that distinguishes us from other primate species, and has allowed our species to survive and eventually build civilizations of unprecedented scale. Humans show par excellence that evolutionary processes are driven not only by scarcity, hierarchy and selfishness, but equally by abundance, cooperation and equality (see AGTRT-BA2).

It was not until 12,000 years ago that humans took a remarkable cultural turn. With the advent of agricultural societies, a hierarchical society based on masculine values such as possession, competition and domination was chosen. Along with the idea that man owns nature, came the idea that the man owns the woman. The androgynous core of humans was split into two pieces that came into conflict with each other. This major cultural shift was eventually possibly triggered by a giant comet impact, which forced humans to live in other ways (see also AGTRT-BA3).

In this piece, I reflect on how patriarchal culture (see AGTRT-BA9) has split our psyche, and how that split has been made possible by the rise of the heteronormative nuclear family. Not only did a culture emerge 12,000 years ago that stifled our androgynous core, but it also curtailed our sexual versatility. Why did this happen, did any of this serve any purpose, and how do we repair the damage?

2. The divisive effect of patriarchy

Philosophers have pointed out that this transition to agricultural society was accompanied by a broader shift in collective consciousness: duality was making its appearance in a general sense. It was the beginning of what was seen as a new civilizing process: humanity had to start tearing himself away from chaotic and unpredictable nature. Humanity had to elevate himself and aimed to rule over nature.

Within this dual thinking about humans and their environment, all sorts of other contradictions could take root. The binary distinction between nature and culture was accompanied by the oppositions object and subject, masculine and feminine, good and bad. This dual thinking was always accompanied by hierarchical thinking: for every contradiction, a subjugator and a subject were designated. Ultimately, the patriarchal system exists by the grace of dichotomies, with one of the extremes at each dichotomy owning the other extreme.

In this dynamic, an entirely new form of society emerged, in which no longer the group or clan was the fundamental building block, but the nuclear family. The androgynous view of humanity, in which each person was seen as both masculine and feminine, was split: the man became masculine, and the woman became feminine. The man and the woman were seen as essentially different, and therefore a perfect complement to each other in the form of a heterosexual couple. Moreover, masculinity was valued higher than femininity: the man ultimately became the boss. See here the basis of the heteronormative family, which is still the foundation of our society today.

3. Growing up in the heteronormative nuclear family

Growing up in this heterosexual nuclear family had major consequences for the development of the child’s psyche. Whereas children in the matriarchal cultures of hunters and gatherers were constantly in contact with men and women in different gender roles, the genders were offered separately for the child in the heteronormative family. The son could identify with the father’s masculinity, and the daughter with the mother’s femininity. There was less and less room for boyish side of girls and the girlish side of boys. Thus, our androgynous psyche was cut into two pieces.

It is precisely the realization about this split in the human psyche that led to modern psychology. The founder of the discipline, Sigmund Freud, famously posited the Oedipus complex as the foundation of his psychoanalysis. The toddler would develop sexual desires toward the parent of the opposite sex, and begin to see the same-sex parent as a rival. The neuroses, psychoses and depressions of his clients, according to Freud, could all eventually be traced in one way or another to this primal complex.

The Oedipus complex has been criticized by modern psychology in many ways. The bond between child and parents is no longer defined in sexual terms, and furthermore, the heteronormative assumptions of the Oedipus complex have now been debunked. But the fundamental insight that psycho-problems of modern people can be traced to the dynamics between the child and parents in the nuclear family still stands. Viewed in this way, the nuclear family as created during the agricultural revolution still leads to trauma today.

4. Healing and integrating a split psyche

German-American psychologist Erich Fromm emphasizes that the Oedipus complex, although a universal phenomenon, has a particularly strong expression in patriarchal societies. The child growing up within the traditional nuclear family inevitably develops inner conflict as gender roles are offered split and hierarchically. Neuroses, according to Fromm, would arise from an inability to break away from the dominant influence of the father figure and the masculinity associated with that role, preventing the expression of the autonomous and androgynous core of the individual.

This interpretation of the modern human as split fits well with Carl Jung’s analytical psychology. He too saw humans as intrinsically androgynous, in psychic distress from growing up in a culture that splits the individual. To heal, the man would have to extract his feminine side (his Anima) and the woman her masculine side (her Animus) from the subconscious and then integrate it into the personality. This process Jung called shadow work (see AGTRT-BA7), and he described it as so tough, destabilizing and complex that it takes a person a lifetime to overcome.

That it can be worth engaging in that process is convincingly demonstrated by American-Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He became famous for his research on the concept of flow, or how we can become happy doing things with our heart and soul. In his search for the roots of human happiness, he arrived at the importance of psychological androgyny: people who have both their masculine and feminine traits developed know best how to tap into their creativity and enter a state of “flow” most easily.

5. Restoring our multifaceted sexuality

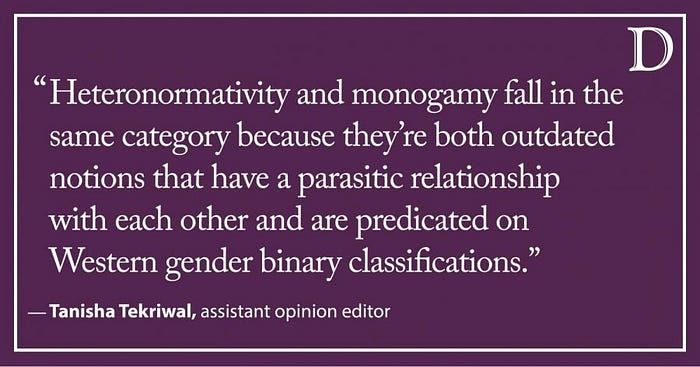

It is not only our gender identity that has been compromised by the patriarchal and heteronormative nuclear family, by the way. Queer theorists point out that patriarchal humans have also fallen far short of his potential in the sexual sphere. French philosopher Guy Hocquenhem, who is also considered the first “queer theorist,” pointed out that modern culture, due in part to a variety of capitalist dynamics, increasingly flattens sexuality into predictable and congealed gender roles. The child, Hocquenhem argues, is “polymorphously perverted” in disposition: it has an inborn creative sexuality. But this sexuality is contained within the heteronormative nuclear family by shame, disgust and morality.

Monogamy too is probably a patriarchal institution with cultural roots in the Neolithic revolution 12,000 years ago. Along with the idea that humanity owns nature, came the idea that the man owns the woman. This also created the idea that sexuality is an exclusive possession. In particular, the husband began to claim sole ownership of his wife’s sexuality. But in matriarchal cultures there was no idea of love or sexuality as an exclusive possession, and this is how humans have lived for hundreds of thousands of years. At the core, human beings are not as monogamous as our culture now often wants to tell us.

This does not mean that human beings do not have exceptional loyalties in love. We know well from primatological and anthropological studies that human beings are pre-eminent creatures of romantic love. Moreover, the idea that there is one “soul mate” on earth for every human being is widespread even outside patriarchal cultures. But the idea that love and sex cannot exist outside this special “soul bond,” and that love is about exclusive possession, that is part of patriarchal oppression.

6. Conclusion

The rise of patriarchal society has had a huge impact on our collective and personal development as human beings. Growing up in the patriarchal and heteronormative nuclear family seems to be an intrinsically traumatic experience, from which the psyche comes out split. This forced a radical break with matriarchal cultures, which were built precisely around the androgynous core of human beings, and where integrating masculinity and femininity was central.

Out of the need to explore how the split psyche can be healed, psychoanalysis eventually emerged. In recent years, I have come to the conviction that healing is possible only if a radically new image of humanity and society is observed. Human beings must again be recognized as intrinsically androgynous: all men are also feminine, and all women are also masculine. It is also necessary to create a form of society that challenges the monogamous and heteronormative nuclear family, and in turn exposes the child to a variety of role models in terms of gender and sexuality while growing up.

By the way, 12,000 years of patriarchal culture did not just do damage. It seems that the transition from cultures revolving around the clan to cultures revolving around the nuclear family have also been emancipating. More space was created for the individual, however split this individual subsequently found himself. The “bicameral mentality,” as so powerfully outlined in Julian Jaynes’ famous book, also created the possibility of integration of those two halves, leading to an ever-expanding individual consciousness over the past several thousand years. This forced a break with the collective culture of the matriarchal hunters and gatherers, which despite its great wisdom could undoubtedly also be perceived as coercive and restrictive at the individual level.

The continued integration of our split psyche is vital for the survival of our species. If the psyche remains split, it can also lead to a species that experiences more and more detachment, sails more and more on ego, and develops less and less sense of the intrinsic connectedness of humans and environment. The insights of Carl Jung and others of his tradition, on how to reintegrate the psyche through “shadow work,” are crucial here (see AGTRT-BA7). With an integrated psyche, we restore our androgynous core and can combine the best of both worlds. The sense of holism and interdependence of the hunters and gatherers can then be combined with the sense of individualism and autonomy of patriarchy. Only then will we really have a solid foundation for the new civilization that both humanity and planet so desperately need.

Leave a Reply